I spent all of Friday writing informational, factual, calming, encouraging, and supportive communications about COVID-19. Emails, an article (Changing Our Habits and Getting Creative: Church in the Age of COVID-19), texts, and about 1,000 more emails. It was a great day. I felt like I was part of helping people navigate this new reality by providing more light than heat.

But my Facebook feed was full of photos of empty store shelves where toilet paper usually was–empty shelves at megastore after megastore.

Which reminded me of a story from my family archives.

My dad was born in occupied Holland during World War II. He is the 4th of 7 kids, so he’s got 3 older brothers who remember growing up during wartime. I’ve told some of the stories elsewhere (here and here), but this one is new to this space. It has to do with toilet paper.

In September 1944, just in time for the Hunger Winter, my dad’s family moved out of the city of Velp and to Ermolo, where my Oma’s sister lived. The Holtrops owned a soup factory and had a big house in the country that could kind of fit the three families who wound up living there that winter. The Nazis had long commandeered all the actually edible food from the factory, but left them fish heads and other odds and ends that they ground and turned into gruel to nourish themselves–they ate in two shifts, younger kids first so they couldn’t see the older kids and adults gag their way through meals. After all, the youngest kids didn’t remember a time when food was delicious.

So of course there was no toilet paper. It would have been an unimaginable luxury. But it’s not like people stop going to the bathroom. Here’s what my uncle told me they did:

- Next to the toilet was a basket with strips of newspaper.

- When you finished your business you folded one and only one strip of paper.

- Then you poked a hole in the middle of the folded strip.

- You pushed your middle fingertip through the hole and used that to wipe your bum–your finger. You’d use your finger.

- Then you used the newspaper to clean off your finger.

- If that didn’t do the job you had to refold the paper and wipe again. With your finger.

Lovely.

Why didn’t they just flat-out use a few of those strips and leave the finger out of it? After all, during the same time period my mother’s family in Michigan used the traditional Sears catalogue in their outhouse.

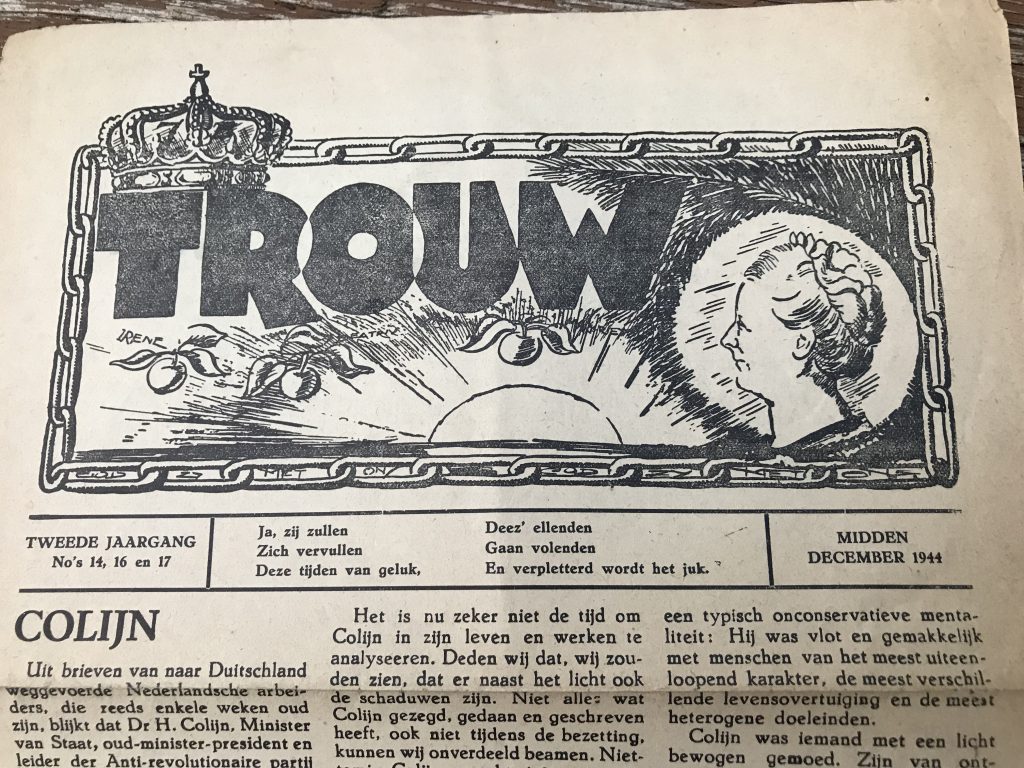

I’m guessing because even the newspaper they had was rare and no, they could not spare a strip. It’s possible that it was often an underground Resistance newspaper, like this one that one of my uncles still has.

I really hope we don’t get to that point in this country. Also, I don’t get a newspaper anymore, so I’d have to use magazines and that sounds like it’d be ouchier. Do I need to stop recycling my magazines now so I have a stack all ready? Then again, if the hoarders keep snapping up all the T.P. maybe I’ll just buy a toilet-top bidet. I will not do what a friend had in the outhouse as a kid and use dry corn cobs!!!

Hoarders of T.P., I know that you’re anxious and you’re trying to control what you can, but you’ve created a problem. When the plush white rolls are back on the shelves, please let others have some. You will be okay. My father’s family all survived their finger-newspaper-toilet-paper ordeal. Well, they survived, but their humor and conversational topics definitely run to the scatalogical.

And now, because I can’t resist, here is what I learned at the Kent County Health Department today that is helping me not panic:

How is the virus transmitted:

- Via droplets that an infected person coughs or sneezes out. The virus is only on our hands and hard surfaces because people cover coughs and sneezes with their hands or not at all, and then touch stuff.

- The contact zone is within 6 feet of an individual with active COVID-19 for more than 10 minutes (walking past someone is not enough to get the virus).

- If someone is infected but not showing symptoms, or if they have mild symptoms, their chance of transmitting the virus is similarly low—the disease is more likely to be transmitted the worse the symptoms are. Read that again. It is very good news, especially about our children as disease vectors. They’re apparently great at spreading the common cold and the stomach flu, less great at spreading COVID-19, because the disease affects them very mildly.

What you can do as an individual:

- Wash your hands often.

- Stay home if you’re sick.

- Cover your mouth with something other than your hand when you cough and sneeze.

- No handshakes. No hugging.

- Limit touches to hard surfaces.

- Spread out! Limit the amount of time you are less than 6 feet away from members of the public for 10 minutes or more. This is the virus transmission zone.

- Before you visit someone, ask if anyone is sick, if anyone has a fever or a new cough. If so, go to a virtual visit (phone call or video chat). If not, maintain safe distance and no handshakes/hugs.

- Disinfect hard surfaces regularly.